Menu

Volume 1, Issue 1

>

A 10-Year Retrospective Pilot Study of Parenteral Diphenhydramine Use in Home Infusion Patients

Introduction: Patients who administer chronic parenteral diphenhydramine are at risk of developing behavioral issues that may represent misuse or abuse. The purpose of this study was to assess potential risk factors and comorbidities for medication noncompliance in the home infusion patient population prescribed parenteral diphenhydramine.

Methods: The study was a retrospective review of the patient population prescribed parenteral diphenhydramine from 2010 to 2020. Data collected from the electronic health record included age, gender, race, indication, type of specialty practice prescribing, duration of therapy, prior history of oral diphenhydramine use, reason for discontinuation, comorbidities, and concomitant medications. Comorbidities assessed included chronic pain, tobacco use, alcohol use, psychiatric disorders, venous access device infections, history of venous thromboembolism, documented overdoses, and history of drug abuse.

Results: Between 2010 and 2020, 101 patients were prescribed scheduled parenteral diphenhydramine. After exclusions, the study group contained 76 patients who met the inclusion criteria. Noncompliance was documented in 27 patients (35.5%). Noncompliance was associated with a diagnosis of mast cell disorder (25.9%) and nausea and vomiting (44.4%). Comorbidities associated with noncompliance included chronic pain (88.9%) and psychiatric disorders. The age range for the compliant group was 20-69 and the noncompliant group was 20-49. Noncompliance was more common in females than males in the study.

Conclusion: The analysis of this patient population supports patients showing signs of parenteral diphenhydramine misuse tend to have higher rate of comorbidities associated with substance use disorders when the duration of therapy was 3 months or longer.

Keywords: Diphenhydramine, abuse, noncompliance, infusion, intravenous, Benadryl®

TABLE 1 | DSM-5 diagnostic criteria for Substance Use Disorder (SUD)2

A problematic pattern of use leading to clinically significant impairment or distress is manifested by 2 or more of the following within a 12-month period:

1. Often taken in larger amounts or over a longer period than was intended

2. A persistent desire or unsuccessful efforts to cut down or control use

3. A great deal of time is spent in activities necessary to obtain, use, or recover from the substance’s effects

4. Craving or a strong desire or urge to use the substance

5. Recurrent use resulting in a failure to fulfill major role obligations at work, school, or home

6. Continued use despite having persistent or recurrent social or interpersonal problems caused or exacerbated by its effects

7. Important social, occupational, or recreational activities are given up or reduced because of use

8. Recurrent use in situations in which it is physically hazardous

9. Continued use despite knowledge of having a persistent or recurrent physical or psychological problem that is likely to have been caused or exacerbated by the substance

10. Tolerance

11. Withdrawal

A small subset of patients who are prescribed diphenhydramine infuse the drug parenterally. For patients that require ongoing administration of parenteral (primarily intravenous, IV) diphenhydramine, home infusion companies can provide patients with the medication and supplies needed to infuse in the home setting. Because this applies to a small number of patients, there is a scarcity of information for dosing and managing them. The risk of SUD related to diphenhydramine has the potential to be especially problematic in the home infusion population when the IV route is utilized, given that this route results in rapid drug bioavailability and is the most efficient route to produce euphoria for many drugs.

An example of an indication that may require chronic parenteral diphenhydramine treatment is Mast Cell Activation Syndrome (MCAS). MCAS includes a heterogeneous group of disorders characterized by the release of mast cell mediators. The disorders are generally considered incurable. Mast cells contain more than 200 mediators, including histamine and tryptase, which contribute to their immune-related and non-immune functioning.10 When activated, mast cells release these mediators, which can result in the signs and symptoms of an allergic reaction which are present in many mast cell disorders. First-line therapies for MCAS include avoidance of triggers and treatment of symptoms. Patients who experience anaphylactic reactions may require epinephrine, steroids, and antihistamines to control symptoms.10

One study of patients with MCAS found that infusing diphenhydramine continuously at 10-14.5 mg/hr appeared safe and effective, and reduced disease flares.11 The study was performed in 10 patients with life-threatening MCAS (aged 18-49; 9 were women) who experienced continuous anaphylactoid or severely dysautonomic flares. At baseline they were treated with subcutaneous epinephrine, H2-Blockers, and intermittent diphenhydramine. Baseline dosing of diphenhydramine among patients was 600-800 mg per day in divided doses (an average of 25-33 mg/hr) administered via IV, intramuscular, or oral routes. All were hospitalized for essentially continuous anaphylaxis and were started on continuous diphenhydramine infusion (CDI) while inpatient. CDI was initially started at 5 mg/hr IV. A rescue dose of diphenhydramine 25-50 mg IV was given with each disease flare, along with an increase of CDI by 1-2 mg/hr. One patient stopped CDI due to reaching 17 mg/hr without effect. Other patients were stabilized on 10-14.5 mg/hr, with a reduction in flare severity and a reduction of flare frequency to 1-4 times per month. Stabilized patients ceased continuous flares within 24 hours and were discharged home on CDI with ambulatory pumps within 48 hours. In the home setting they had diphenhydramine 10-25 mg IV available as needed for flares. Patients were followed for 0.5-21 months with continued reduction in flares (1-4 times per month). The author of the study reported no evidence of tolerance or waning of effect during follow up.11

It is the experience of pharmacists at a regional home infusion provider that the patient population is at risk of developing behavioral issues with chronic parenteral diphenhydramine that may represent misuse or abuse. Aside from the MCAS study above, there is little information available to guide clinicians on the optimal dosing of outpatient chronic parenteral diphenhydramine. In addition, there is a lack of clinical information and guidance of the risk factors for and treatment of diphenhydramine abuse. Therefore it was decided to conduct a retrospective analysis of our patient population to determine next steps.

To review the patient population who were prescribed parenteral diphenhydramine from 2010 to 2020 in order to assess potential risk factors or comorbidities associated with noncompliance. To assess the direction of future research in the area of SUD related to chronic parenteral diphenhydramine use.

The purpose of this study was not to diagnose drug abuse or SUD.

In the first quarter of 2021, the pharmacists conducted a retrospective review of patients who had been prescribed scheduled parenteral diphenhydramine (predominantly intravenous) from 2010 to 2020. Patients of all ages were included if any doses were dispensed to them during that time period. Patients were excluded if they only received oral diphenhydramine, if diphenhydramine was prescribed as a premedication for an intermittent specialty medication (ex: prior to intermittent infliximab infusions), or if it was dispensed as part of an anaphylaxis kit.

Data collected included age at start of treatment with parenteral diphenhydramine, gender, race, indication, type of specialty practice prescribing, duration of therapy, prior history of taking oral diphenhydramine, and reason for discontinuation. Comorbidities assessed included chronic pain, tobacco use, alcohol abuse, various psychiatric disorders, history of line infections, history of venous thromboembolism, documented overdoses, and history or family history of drug abuse. Concomitant medication drug classes were also assessed.

Because of the retrospective nature of this study and the limited diagnostic information available, few criteria used in the diagnosis of SUDs could be evaluated (see Table 1).2 Rather than trying to diagnose abuse or a SUD, the pharmacists collected information about patient noncompliance that indicated misuse for this pilot study.

For the purpose of our study, noncompliance was defined as meeting at least one of the following criteria: documentation in the patient electronic medical record of more than 1 early refill request; the documented intervention of a home infusion clinician related to problems with diphenhydramine therapy; necessity of a compliance contract related to diphenhydramine noncompliance; documentation in an alerts field of noncompliance or early refills; other documentation in the electronic medical record stating the prescriber was aware of noncompliance. For this study, patients will be referred to as “noncompliant” if they met any of the criteria above, and will be labeled as “compliant” if they did not have documentation of noncompliance as above.

Institutional Review Board (IRB) Status

The research involved secondary data analysis where the data set was deidentified before analysis and recorded in a manner where the resulting data contained no information that could be linked directly or indirectly to the identity of the subjects.

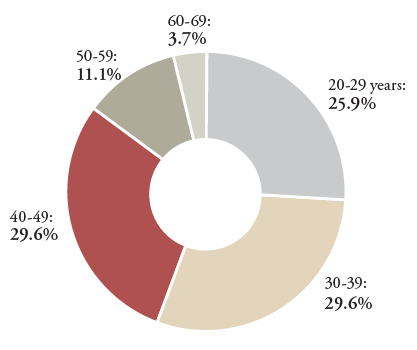

Between 2010 and 2020, 101 patients were prescribed scheduled parenteral diphenhydramine. After excluding patients as described above, 76 met inclusion criteria (see Table 2). After data collection and analysis, 49 patients (64.5%) were determined to be compliant and 27 (35.5%) patients had documentation of noncompliance. Of the 76 total patients, 58 (76.3%) were female, 17 (22.4%) were male, and 1 (1.3%) was transgender. Of the patients who had documentation of noncompliance, 24 (88.9%) were female and 3 (11.1%) were male. The majority of compliant patients fell into a wide range of age groups from age 20 to 69, while noncompliant patients were mostly concentrated between the ages of 20 and 49 (see Figure 1). Given the small numbers of patients who were non-white, we were unable to assess trends based on race.

TABLE 2 | Patient Demographics

All Patients, n=76 |

Compliant, n=49 |

Noncompliant, n=27 |

||

|---|---|---|---|---|

|

|

n(%)

|

n(%)

|

n(%)

|

|

|

Total Patients

|

76 (100%)

|

49 (64.5%)

|

27 (35.5%)

|

|

|

Sex

|

||||

|

Male

|

17 (22.4%)

|

14 (28.6%)

|

3 (11.1%)

|

|

|

Female

|

58 (76.3%)

|

34 (69.4%)

|

24 (88.9%)

|

|

|

Transgender (F to M)

|

1 (1.3%)

|

1 (2.0%)

|

0

|

|

|

Age*

|

||||

|

0-9

|

4 (5.3%)

|

4 (8.2%)

|

0

|

|

|

10-19

|

3 (3.9%)

|

3 (6.1%)

|

0

|

|

|

20-29

|

15 (19.7%)

|

8 (16.3%)

|

7 (25.9%)

|

|

|

30-39

|

16 (21.1%)

|

8 (16.3%)

|

8 (29.6%)

|

|

|

40-49

|

17 (22.4%)

|

9 (18.4%)

|

8 (29.6%)

|

|

|

50-59

|

11 (14.5%)

|

8 (16.3%)

|

3 (11.1%)

|

|

|

60-69

|

8 (10.5%)

|

7 (14.3%)

|

1 (3.7%)

|

|

|

70-79

|

1 (1.3%)

|

1 (2.0%)

|

0

|

|

|

80-89

|

0

|

0

|

0

|

|

|

90-99

|

1 (1.3%)

|

1 (2.0%)

|

0

|

|

|

Race

|

||||

|

Native American

|

1 (1.3%)

|

0

|

1 (3.7%)

|

|

|

Black/African American

|

1 (1.3%)

|

1 (2.0%)

|

0

|

|

|

Hispanic or Latino

|

2 (2.6%)

|

1 (2.0%)

|

1 (3.7%)

|

|

|

White (Non-Hispanic, Non-Latino)

|

64 (84.2%)

|

40 (81.6%)

|

24 (88.9%)

|

|

|

Unknown

|

8 (10.5%)

|

7 (14.3%)

|

1 (3.7%)

|

*Age at start of treatment with parenteral diphenhydramine

FIGURE 1 | Percentage of Noncompliant Patients by Age Range (n=27)

The most common indications for parenteral diphenhydramine therapy for all patients were anti-infective premedication and nausea/vomiting (see Table 3). A higher percentage of compliant patients had an indication of anti-infective premedication vs. noncompliant patients ([n=23, 46.9%] vs. [n=4, 14.8%]). A higher percentage of noncompliant patients vs. compliant patients had an indication of mast cell disorder ([n=7, 25.9%] vs. [n=2, 4.1%]) and nausea/vomiting ([n=12, 44.4%] vs. [n=15, 30.6%]).

TABLE 3 | Indication for Parenteral Diphenhydramine Therapy

All Patients, n=76 |

Compliant, n=49 |

Noncompliant, n=27 |

|

|---|---|---|---|

|

Abdominal Pain, n (%)

|

1 (1.3%)

|

0

|

1 (3.7%)

|

|

Anti-infective premedication, n (%)

|

27 (35.5%)

|

23 (46.9%)

|

4 (14.8%)

|

|

End of Life Care and Comfort, n (%)

|

8 (10.5%)

|

7 (14.3%)

|

1 (3.7%)

|

|

Idiosyncratic anaphylactoid events, n (%)

|

1 (1.3%)

|

0

|

1 (3.7%)

|

|

Itching, n (%)

|

2 (2.6%)

|

2 (4.1%)

|

0

|

|

Mast Cell Disorder, n (%)

|

9 (11.8%)

|

2 (4.1%)

|

7 (25.9%)

|

|

Nausea/vomiting (+/- itching), n (%)

|

27 (35.5%)

|

15 (30.6%)

|

12 (44.4%)

|

|

Rash, n (%)

|

1 (1.3%)

|

0

|

1 (3.7%)

|

When analyzing comorbidities (see Table 4), noncompliant patients tended to have chronic pain more frequently than compliant patients ([n=24, 88.9%] vs. [n=26, 53.1%]). Noncompliant patients had higher rates of psychiatric disorders except for bipolar disorder ([n=1, 3.7% for noncompliant] vs. [n=3, 6.1% for compliant]). Noncompliant patients had rates of anxiety and depression that were more than 20% higher than compliant patients ([n=15, 55.6%] vs. [n=15, 30.6%] for anxiety, and [n=16, 59.3%] vs. [n=17, 34.7%] for depression). A history of PTSD was identified in 18.5% (n=5) of noncompliant patients vs. 8.2% (n=4) of compliant patients. Noncompliant patients tended to have higher rates of history of venous thromboembolism (VTE) compared to compliant patients ([n=12, 44.4%] vs. [n=16, 32.7%]). There was a history of line infections in 25.9% (n=7) of noncompliant patients, compared to 6.1% (n=3) of compliant patients. Due to low incidences, it was not feasible to see trends in documented overdoses or history of drug abuse.

TABLE 4 | Comorbidities

All Patients, n=76 |

Compliant, n=49 |

Noncompliant, n=27 |

|

|---|---|---|---|

|

|

n(%)†

|

n(%)†

|

n(%)†

|

|

Chronic Pain

|

50 (65.8%)

|

26 (53.1%)

|

24 (88.9%)

|

|

Tobacco Use (Past or Present)

|

18 (23.7%)

|

11 (22.4%)

|

7 (25.9%)

|

|

Alcohol Abuse

|

3 (3.9%)

|

2 (4.1%)

|

1 (3.7%)

|

|

Anxiety

|

30 (39.5%)

|

15 (30.6%)

|

15 (55.6%)

|

|

Depression

|

33 (43.4%)

|

17 (34.7%)

|

16 (59.3%)

|

|

Bipolar Disorder

|

4 (5.3%)

|

3 (6.1%)

|

1 (3.7%)

|

|

ADHD

|

6 (7.9%)

|

2 (4.1%)

|

4 (14.8%)

|

|

Eating Disorder

|

3 (3.9%)

|

1 (2.0%)

|

2 (7.4%)

|

|

PTSD

|

9 (11.8%)

|

4 (8.2%)

|

5 (18.5%)

|

|

Schizophrenia

|

2 (2.6%)

|

1 (2.0%)

|

1 (3.7%)

|

|

History Line Infections

|

10 (13.2%)

|

3 (6.1%)

|

7 (25.9%)

|

|

History VTE

|

29 (38.2%)

|

16 (32.7%)

|

12 (44.4%)

|

|

Documented Overdoses

|

1 (1.3%)

|

1 (2.0%)

|

0

|

|

History of Drug Abuse*

|

4 (5.3%)

|

2 (4.1%)

|

2 (7.4%)

|

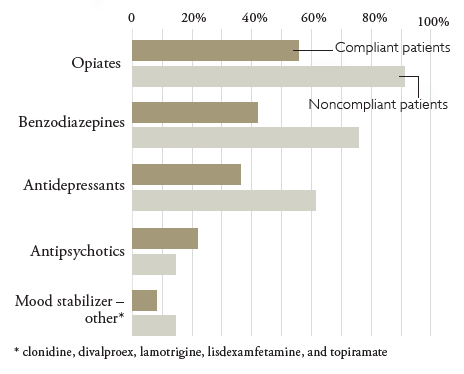

FIGURE 2 | Concomitant Medications: Compliant vs. Noncompliant Patients (n=76)

There appears to be a strong correlation between duration of parenteral diphenhydramine therapy and compliance, as defined in this study (see Table 5). The majority of compliant patients had a duration of therapy of less than 2 weeks (n=20, 40.8%), while the majority of noncompliant patients were on parenteral diphenhydramine for greater than 3 months (n=23, 85.2%).

TABLE 5 | Duration of Parenteral Diphenhydramine Therapy

All Patients, n=76 |

Compliant, n=49 |

Noncompliant, n=27 |

|

|---|---|---|---|

|

|

n(%)

|

n(%)

|

n(%)

|

|

< 2 weeks

|

21 (27.6%)

|

20 (40.8%)

|

1 (3.7%)

|

|

2 weeks to 1 month

|

10 (13.2%)

|

9 (18.4%)

|

1 (3.7%)

|

|

1 - 2 months

|

3 (3.9%)

|

3 (6.1%)

|

0

|

|

2 - 3 months

|

5 (6.6%)

|

3 (6.1%)

|

2 (7.4%)

|

|

> 3 months

|

37 (48.7%)

|

14 (28.6%)

|

23 (85.2%)

|

The results of this study reveal trends in the patient population, but based on the small sample size, significance differences can not be calculated. Furthermore, the correlations presented do not prove causation. Without further analysis and formal diagnosis, it is not possible to determine whether the noncompliance seen in these patients represents a SUD, or if the patients are exhibiting drug seeking behavior due to inadequate treatment of their underlying disease.

Unfortunately, there are no guidelines for the management of patients prescribed chronic diphenhydramine therapy. Other drug therapies, such as opiates, have guidelines available to direct prescribers on baseline patient evaluations (including benefit-to-harm analysis), obtaining informed consent (including education about goals, expectations, risks and alternatives), guidance on dosing and titration, patient monitoring, protocols for patients with history of drug abuse or psychiatric issues, managing adverse events, potential adjunctive therapies, driving and work safety, implications in pregnancy, the need for an identified managing provider, and guidance on when a specialist consult is needed.12 General practices to reduce the risk of drug misuse include starting with the lowest possible dose, titrating doses slowly, and limiting the duration of therapy if possible. Early refills should be avoided.12

Despite having risk factors for SUD, some patients require treatment with medications that have abuse potential. Treatment with diphenhydramine is often necessary for the treatment of intractable vomiting or mast cell disorders. Guidelines are needed to direct clinicians on how to best manage these patients.

Limitations of this study include a small patient population and limited clinical documentation. Because of the lack of understanding about the potential for the misuse of parenteral diphenhydramine, these patients were not evaluated for diphenhydramine-related SUD by their providers in almost all cases. The retrospective nature of this study excluded patient interviews or requests for additional documentation from referring providers. The authors of this study acknowledge that based on the established definitions of compliant and noncompliant and the clinical information available, it cannot be concluded that noncompliant patients misused or abused diphenhydramine therapy.

The analysis of this patient population supports that patients showing signs of parenteral diphenhydramine misuse tend to have higher rates of many of the comorbidities associated with SUD (depression, anxiety, PTSD, eating disorders, schizophrenia, and ADHD).8 They also had higher rates of multiple risk factors for sedative-hypnotic prescription drug abuse (especially female sex and psychiatric symptoms).9 In addition, patients tended to be younger adults (aged 20 to 49); they had higher rates of chronic pain; and they had higher rates of line infections. Medication assessment revealed higher rates of opiate, benzodiazepine, and antidepressant use. The most common indications for parenteral diphenhydramine in this patient subset were mast cell disorders and nausea/vomiting, and the duration of therapy was greater than 3 months in most cases.

Further research and guidance regarding chronic parenteral diphenhydramine use in the home setting is needed. Research and guidance should include analysis of larger patient populations, risk factors for diphenhydramine misuse, benefit-to-harm analysis, optimal dosing and titration, patient monitoring, protocols for patients at risk of diphenhydramine abuse, management of adverse events, and potential alternative and adjunctive therapies. In the meantime, patients requiring chronic parenteral diphenhydramine should be maintained at the lowest possible dose, and the selection of method of administration should include considerations of abuse potential. Pharmacists and patient providers should work collaboratively to optimize treatment regimens in these patients to prevent the misuse or abuse of diphenhydramine.

| Cookie | Duration | Description |

|---|---|---|

| cookielawinfo-checbox-analytics | 11 months | This cookie is set by GDPR Cookie Consent plugin. The cookie is used to store the user consent for the cookies in the category "Analytics". |

| cookielawinfo-checbox-functional | 11 months | The cookie is set by GDPR cookie consent to record the user consent for the cookies in the category "Functional". |

| cookielawinfo-checbox-others | 11 months | This cookie is set by GDPR Cookie Consent plugin. The cookie is used to store the user consent for the cookies in the category "Other. |

| cookielawinfo-checkbox-necessary | 11 months | This cookie is set by GDPR Cookie Consent plugin. The cookies is used to store the user consent for the cookies in the category "Necessary". |

| cookielawinfo-checkbox-performance | 11 months | This cookie is set by GDPR Cookie Consent plugin. The cookie is used to store the user consent for the cookies in the category "Performance". |

| viewed_cookie_policy | 11 months | The cookie is set by the GDPR Cookie Consent plugin and is used to store whether or not user has consented to the use of cookies. It does not store any personal data. |